Remember I posted about my article Love, Rage and the Occupation, which got published on Journal of Bisexuality? So, I discovered that I can put the text on my blog without breaching copyrights. Now everyone can read it for free. Hooray!

Since this article is very long, I’m going to be posting it in parts over the next few weeks. This is part 1 out of maybe 8-9, so stay tuned for further updates.

Love, Rage and the Occupation: Bisexual Politics in Israel/Palestine

Introduction: who I am and why I’m writing

My name is Shiri. I’m 28 years old at the time of this writing [I wrote this last year], I live in Israel/Occupied Palestine, and have been an activist on feminist, queer, anti-occupation and animal rights issues for nearly seven years now. I’ve been a bisexual activist for almost three years. This text tells my story as a bisexual activist, and through it, I hope, also the story of the bisexual movement in Israel so far. In addition, I hope to show my readers the strands of Israeli militarism and its culture of violent and racist occupation of Palestine and the Palestinian people, which weave through all of our lives and all of our experiences here. With this I hope to achieve two things: firstly, to deconstruct the false separation between the two fields of “LGBT rights”1 and anti-war activism, emphasizing connections between oppressed groups and their struggles; secondly, to promote the principles of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement, encouraging actions of solidarity with the Palestinian people and non-violent struggle against the Israeli occupation.2

The BDS is a call made by over 60 Palestinian academic, cultural and other civil society federations, unions, and organizations (and supported by hundreds of organizations worldwide), for a comprehensive economic, cultural and academic boycott of Israel. The BDS lists three goals: ending the occupation and colonization of all Arab lands occupied by Israel in June 1967; full equality for Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel; and acknowledging the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN Resolution 1948. The BDS is a global non-violent movement, opposed to all forms of violence and racism (including antisemitism). However, the BDS not only focuses on ending the occupation, but also in building a better society, thus the BDS endorses and is endorsed by many queer, feminist and other organizations.

On the queer side of the BDS, we emphasize the connection between the occupation and the oppression of Palestinian LGBTQ people both in Israel and in Palestine. The occupation does not differentiate between queers and non-queers – thus, under the occupation, Palestinian LGBTQ people are denied even the most basic human rights such as freedom of movement, medical care, education, etc. Palestinian LGBTQ’s living inside Israel face systematic, legalized apartheid policies which discriminate against them in all walks of life, rendering them de facto second class citizens.

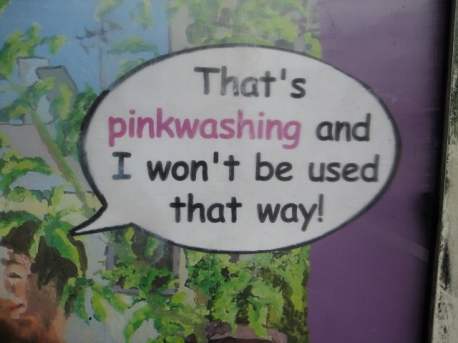

In addition, both Palestinian and Israeli LGBTQ’s are being cynically used by the Israeli government and Israeli propaganda in order to “pinkwash” Israel’s international public image. Israeli government, through the Ministry of Tourism, makes use of the relative tolerance towards Jewish LGBTQ’s (especially in Tel Aviv), as a way of diverting attention from the many Israeli war crimes performed in Gaza, the occupied Palestinian territories and inside Israel itself. Thus, on the backs of both the Jewish and Palestinian LGBTQ communities, Israeli propaganda can market a false image of Israel as a “liberal” “progressive” “gay haven,” while demonizing Arabic Middle Eastern cultures and presenting them as inherently homophobic – an Islamophobic notion whose goal is to further justify Israeli war crimes in Gaza and the occupied territories as well as against Palestinian citizens of Israel.

The cost of pinkwashing takes its toll not only from Palestinians, but also from Jewish LGBTQ people, as incidents of violence, discrimination, harassment and mistreatment are discretely silenced so as to prevent injury of Israel’s “progressive” image. In addition, pinkwashing helps the government in convincing the Jewish LGBTQ community that no further rights need to be won, that all is well and that there’s nothing left for us to do but join their shiny new brand of homonationalism. From a bisexual and transgender standpoint, it’s also worth noting that the process of pinkwashing not only erases the fact that bisexuals and transgenders have no legal recognition or rights in Israel (contrary to gays and lesbians), but also erases and silences inner community violence against us – perpetuated not only for our being bisexuals and transgenders, but also for our activist communities’ extensive involvement in the struggle against the occupation.3

This article will consist of a sequence of stories from my personal history as an activist.4 The reason why I chose to tell this story from my own perspective rather than take the more ‘dignified’ stance of an academic researcher is threefold. Firstly, by telling the story from my personal point of view, I denounce a single, unified, master-narrative. Whereas the events that I describe have certainly existed in – and influenced – what is so often called the “public sphere”, I still acknowledge that some people may have experienced the events I describe, in ways that are different from my own. Different people have also given different interpretations to the meanings of the same events, including ones different from mine. Experiences and views vary, and I would be reluctant to claim my view as a definitive one.

Secondly, living in a patriarchal, masculinist world, we all learn to appreciate certain values over others: objectivity over subjectivity, universal over personal, rational over emotional. The values associated with masculinity are socially rewarded with respect, dignity and status, and are attributed more importance (both within and without the academia). On the other hand, the values associated with femininity are perceived as flawed, undignified and often even inappropriate. Indeed, in polite “Western” society, speaking of one’s feelings or personal life is often frowned upon. Of course, these values are also racially charged: the former, masculine ones often linked to whiteness and “Western-ness”, and the latter, feminine ones, to “race” and “third-world-ness”. Thus, it is my intent to undermine and subvert these values through use of a personal narrative and emotional writing. By this I mean to suggest that emotions, subjectivity and personal perspectives are central to our experiences as people and should be respected as crucial to our understandings of the world. I feel that to claim a space, and to incorporate these values in my writing is a political act of feminist and anti-racist subversion.

Thirdly, telling the story through my eyes is conducive to my understanding that, as us feminists like to say, the personal is political. In this, I not only mean that ‘exterior’ circumstances shape and often determine our lived experiences, nor only do I mean that the experiences in our lives have political meanings – I also mean to suggest that for many of us, who devote our lives to activism – the separation between the “personal” and the “political”, the “private” and the “public” – is neigh nonexistent. Is suffering physical violence by the police more or less personal than suffering violence at home? Do one’s friends and lovers touch our feelings more deeply in bed than on the streets? Is the struggle against our families, our teachers and our peers more or less painful, more or less passionate, more or less intimate, than the struggle against the system, the government and heteropatriarchy? Activists embody, in our physical bodies and in our selves, the lack of distinction between these “two” imagined worlds. Nothing is personal that is not political. Nothing is political that is not personal. In addition, I would like to think of this lack of differentiation as bisexual in character, marking a collapse of boundaries, a destabilization of binaries and a breaking down of order.

A disclaimer should be made as to why I’m writing these stories – what should be made of them, and what should not: This text is not here to tell you about a strange land, far far away. It is not here to be exoticized as the tale of a “developing” bisexual movement in a “developing” or “backward” part of the world, where brown skinned “savages” fight with one another. The call for solidarity under the BDS (or for solidarity with the Israeli bisexual movement) is not to be taken as an appeal to a higher, whiter moral guardian. Nor is this text, in its better parts, to be taken as buying into Zionist pinkwashing propaganda of presenting Israel as the friendly “progressive” “LGBT” haven it markets itself to be.

What this text is about is the violence and difficulties that we all experience in our communities. It is here to enlighten similarities rather than differences – the difficulties described herein are not unique, but exist everywhere, should be addressed by us all.5 This text is here to encourage political responsibility and accountability in all of us, in our communities and in our countries – the Israeli occupation could not have existed without the active financial and political support given it by the USA, UK and other “Western” countries. This text is also here as an alternative activist model for whomever might want to start their own radical bisexual movement, in their own area. It is here as inspiration for change within the existing bisexual movement in the USA and Europe, in terms of critical perspectives, ideology and activist methods. And finally, it is here for whomever wishes to learn or study about Israel, its bisexual movement, its radical queer history and the queer struggle against the occupation.

Some of the experiences I describe in these stories are both difficult, violent and traumatic (including descriptions of physical violence, death and grief). If you think that any of the stories might trigger past traumas for you or make you otherwise uncomfortable, please consider reading this piece (or the relevant parts of it – especially the 7th and 8th stories) somewhere that feels safe for you and at a time when you have emotional support available should you need it.

Next – Part two

First story (2006): Queeruption

Footnotes:

1 The term “LGBT rights” is in quotations because I dispute both terms. Oftentimes I find that what is commonly called the “LGBT” movement usually stands only for the interests of white cisgender gay males, creating the impression of what I like to call the “GGGG” movement. As to “rights”, the word points to a liberal discourse focusing on legislation and government sanction, such that is accepting of current social order as basis for its claims. I prefer the stance of liberation in lieu of “rights” – a radical change of social order, such that we are all liberated from current power structures (including government, white heteropatriarchy and capitalism).

2 A parliament bill was recently approved by the Israeli Knesset, threatening various sanctions upon anyone promoting any type of boycott against Israel, its institutions or any particular place within it. Under this law, by publishing this article, I might be subject to such sanctions. This is all the more reason to proceed with the boycott, with its promotion and with the struggle against Israeli occupation and fascist policies. For more on Israeli government sanctions on the freedom of speech, see: Coalition of Women for Peace. (2010). All-Out War: Israel Against Democracy. Retrieved from: http://coalition.s482.sureserver.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/AllOutWar-internet-ENG.pdf

3 For more about the queer BDS, see: Palestinian Queers for BDS (http://pqbds.wordpress.com) and: Israeli Queers for Palestine (http://israeliqueersforpalestine.wordpress.com).

4 As this is a personal narrative, I realize that there may be some theoretical gaps for readers who are unfamiliar with the material. I endeavour to fill these gaps somewhat using small interludes throughout the text, however the scope of this work is insufficient to fill all. Therefore, for those who feel in want of more in-depth theoretical explanations, I strongly advise following the references in the footnotes.

5 For an excellent example on police and inner-LGBT brutality against radical queer groups, see: Bernstein Sycamore M. (2004). Gay Shame: From Queer Autonomous Space to Direct Action Extravaganza. In Bernstein Sycamore M. That’s Revolting (268-295). Soft Skull Press. (A summarized version of this text may be found online at: http://www.gayshamesf.org/slingshotgayshame.html).

[This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Bisexuality Volume 12, Issue 1, 2012. The Journal of Bisexuality article is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15299716.2012.645722]

4 thoughts on “Love, Rage and the Occupation: Bisexual Politics in Israel/Palestine – Part 1”